Post 5 - Community Water Management, A Solution Towards Sustainable Water Development In Africa?

|

| Picture: Handpump |

Ethiopia's rural water strategy (RWS) is based on 'the development orthodoxy' principles (Page, 2003) - community management. It entrusts users with sustainable operations and maintenance (O&Ms) responsibility (Ludi et al., 2013; Hutchings et al., 2015), aligning with governmental bodies and NGO's promotion of local empowerment. Despite being a cost-efficient solution for authorities, sub-Saharan revealed a third of RWS systems were non-functional (Baumann, 2006). The 2016 El Niño crisis in Ethiopia exposed the inadequacy of the RWS, with 50% of hand-dug wells and 42% of other water points non-functional, leaving 43% of the population below the emergency six-litre threshold (Florence, 2019) - underscoring the limitations in RWS’ "informality and voluntarism" (Moriarty et al., 2013).

To address RWS failure, we examine Hutchings et al. (2015) study on 174 successful community management cases worldwide. Notably, among the 72 high-performing cases, 90% attributed external agencies for post-construction support. Fig1 depicts how the lifecycle of handpumps is directly correlated with the amount of support received.

|

| Fig1: Handpump Lifecycle and Support |

This successful framework is called the Community Plus model; it requires collective initiative, strong leadership, transparency, and outsourcing of O&Ms to external institutions (Baumann, 2006) (Fig2).

|

| Fig2: Framework for Success |

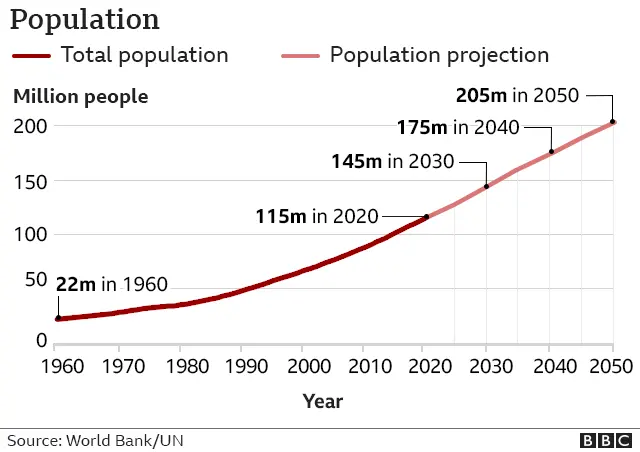

Implementing such frameworks proves challenging in Ethiopia. To begin with, Ethiopia’s Government places minimal political prioritisation and little funding (Behailu et al., 2016) on O&M. They prioritise coverage expansion to address low-population water access stemming from the exponential population growth (Fig3) and high rural internal migration (Lockwood et al., 2017). They aim to realise Ethiopia's Growth and Transformation Plan, providing 85% of the rural population access to 25 litres of potable water per capita per day by 2020 (Florence, 2019).

|

| Fig3: Ethiopia's Population and Projections |

Ethiopia’s RWS primary shortcoming is the community's inability to cover O&M, as up to 90% of Ethiopia's rural populations are farmers who cannot afford the monthly bill due to their dependence on seasonal crop yields. Such communities don't see the value of paying for safe water, as they often opt for free traditional water sources. This hinders spare parts procurement and hiring paid-for staff to take on critical aspects of O&M (Moriarty et al., 2013) (Fig4); in Oromia alone, seven cranes are shared to maintain large distances of 18 zones with hundreds of schemes. Ethiopia's mountainous landscapes make logistics, communication, and transport even daunting.

|

| Fig4: Mismanaged Water-System's Vicious Cycle |

Community management decision-making is difficult, given the low education, lack of technical knowledge and members juggling competing work priorities. The unpredictable spare part cost further complicated the budgeting and cost recovery process (Akale & Kebede, 2019). Collective equitable participation from disadvantaged groups and women is limited, as women's involvement is often limited to cleaning borehole areas (Hutchings et al., 2015).

Ethiopia's RWS highlights the O&M complexity as each RWS requires tailor-made external support to cater to each community's specifics. Luckily, the GoE and NGOs have begun actively addressing these challenges seriously and assisting in setting up small private O&M entrepreneurs for long-term sustainability of RWS while creating employment.

Comments

Post a Comment